First steps with Faiss for k-nearest neighbor search in large search spaces

tl;dr: The faiss library allows to perform nearest neighbor search in an efficient way, scaling to several million dense vectors. Go straight to the example code!

Vector embeddings and search

A common procedure used in information retrieval and machine learning is to represent entities with low-dimensional dense vectors, also known as embeddings. These vectors typically have a number of dimensions between 25 and 1000 (we call them dense because the utmost majority of their components are non-zero, so they are not sparse).

Researchers have devised ways to compute vector embeddings for different kinds of entities: nowadays embeddings can be constructed for words, entire text documents, entire images, local features in images, nodes in graphs, and more (as testified by the existence of very many “2vec” models).

Such vector representations have interesting properties (think word2vec’s). One basic property is that similar vectors (i.e. vectors close to each other according to a given similarity metric, like the cosine similarity or the Euclidean distance) represent entities that are somehow closely related to each other. This feature is important as it unlocks the possibility of searching for entities relevant for a given query entity.

For example, let’s consider words. If we want to look up words that are related to a given word (e.g. synonyms), we can

- Compute appropriate vector representations

xbfor all $N$ words in a vocabulary $S$; - Look up the vector representation

xqof the query word; - Select the vectors that are closest to

xq(according to some given metric), among all those at step 1; - Retrieve all words represented by the vectors selected in step 3 (those are the final results).

One could carry out a similar procedure using documents (Elasticsearch now supports this to retrieve similar documents), images (search engines for images can work this way) or small details in images (as done in feature matching).

If we can compute a “good” vector representation for entities (step 1 above) and have a viable algorithm to identify vectors close to a query vector (step 3, also known as k-nearest neighbors search, or k-NN search) we can build an efficient search engine.

In what follows we assume that step 1 has been solved for us and concentrate on how to carry out step 3, using Python and focusing on the cases of large $N$. Solving k-NN search has great industrial relevance: companies such as Spotify and Facebook have been developing libraries to solve this problem efficiently.

k-nearest neighbors search in Python

Given a set $S$ of $d$-dimensional $N$ vectors xb (the search space) and a query vector xq, how can we find its nearest neighbors in $S$ using Python?

If $N$ is large, the computation can be expensive, so it’s beneficial to leverage some level of optimization offered by dedicated numerical libraries.

In what follows we’ll analyze a solution using numpy, scikit-learn and finally faiss, that can search among several millions of dense vectors. We will use the Euclidean distance as similarity metric for vectors (code could be modified to use other metrics).

Linear search using numpy

One simple strategy is to compute the distance from xq to every other vector in $S$, and identify the $k$ vectors that have minimum distance. As all the possible matches are evaluated, this is also called brute force search.

This operation requires the computation of $N$ distances and then finding the bottom $k$ values.

Once we have all the components of the vectors in $S$ stored in a numpy array xb, we can compute the indices of the k-nearest neighbors with

import numpy as np

N = 1000000

d = 100

k = 5

# create an array of N d-dimensional vectors (our search space)

xb = np.random.random((N, d)).astype('float32')

# create a random d-dimensional query vector

xq = np.random.random(d)

# compute distances

distances = np.linalg.norm(xb - xq, axis = 1)

# select indices of vectors having the lowest distances from the query vector (sorted!)

neighbors = np.argpartition(distances, range(0, k))[:k]

This is fairly straightforward, but it’s interesting to note that we’re using numpy.argpartition to select the indices of the vectors having the lowest distances (numpy.argpartition does the job efficiently on a CPU as it uses the introselect algorithm). Mind that we’re calling the function using range(0, k) as argument, because otherwise the neighbor indices wouldn’t be sorted by distance from xq!

This strategy is simple (it takes 2 lines of code!) but it requires the entire matrix of vectors to be stored in memory. This means that if the space taken in memory by the xb is above the RAM available, the code won’t run!

Search with scikit-learn

scikit-learn provides a dedicated class to solve the problem, sklearn.neighbors.NearestNeighbors. Searching in this case would look like

from sklearn.neighbors import NearestNeighbors

# set desired number of neighbors

neigh = NearestNeighbors(n_neighbors=k)

neigh.fit(xb)

# select indices of k nearest neighbors of the vectors in the input list

neighbors = neigh.kneighbors([xq], return_distance = False)

Using sklearn offers some advantages, as it automatically employs heuristics to determine if it should resort to computational tricks (like k-d trees) to reduce the number of distance calculations. A variety of metrics can be chosen to pick neighbors, and searching using multiple query vectors can be done by adding more vectors in the list passed to neigh.kneighbors().

One can also save to disk neigh for further reuse with

from joblib import dump, load

dump(neigh, "my_fitted_nn_estimator")

and load it again with

neigh = load("my_fitted_nn_estimator")

Last but not least, the sklearn-based code is arguably more readable and the use of a dedicated library can help avoid bugs (see e.g. the numpy.argpartition caveat above) that may be inadvertently introduced in the code.

However, if the search space is large (say, several million vectors), both the time needed to compute nearest neighbors and RAM needed to carry out the search may be large. We thus need additional tricks to solve the problem!

Search with faiss, and scale beyond RAM constraints

One library that offers a more sophisticated bag of tricks to perform the search is faiss.

From their wiki on GitHub: “Faiss is a library for efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors. It contains algorithms that search in sets of vectors of any size, up to ones that possibly do not fit in RAM”.

The possibility of searching in vector sets not fitting in RAM is useful and numpy, sklearn, even Spotify’s annoy can’t do that AFAIK.

Exact brute-force searches like the one done above with numpy can be replicated with the syntax:

import faiss

index = faiss.index_factory(d, "Flat")

index.train(xb)

index.add(xb)

distances, neighbors = index.search(xq.reshape(1,-1).astype(np.float32), k)

So, why the fuss? Well, what’s cool about faiss is that it allows to strike a balance between accuracy (i.e. not returning all the true k-nearest neighbors, but just “good guesses”), speed and RAM requirements when dealing with large $N$. This is possible thanks to the precomputation of data structures (the indices) that store vectors in a clever way, and by tweaking their parameters. The library is also designed to take advantage of GPU architectures to speed up search.

One class of tricks used to speed up search is the pruning of $S$, i.e. dividing up $S$ into “buckets” (Voronoi cells in $d$ dimensions) and probing for nearest neighbors only some number nprobe of such buckets. While this procedure can miss some of the true nearest neighbors, it can greatly accelerate the search.

faiss also implements compression strategies to speed up the distance computation and reduce memory use. By applying methods like product quantization (PQ) it is possible to obtain distances in an approximate (but faster) way, using table lookups instead of direct computation.

A more concrete case: searching in a 1M dataset with faiss

The choice of which “tricks” to use for a specific problem depends on considerations about the raw input (dataset size, the spatial organization of the vectors), the available hardware (CPU vs GPU, available RAM, single node vs distributed processing), desired accuracy, speed, and total number of searches we need to perform.

The faiss wiki on GitHub can help evaluate the different options.

Let’s examine more in detail a case in which:

- $N \approx 10^6$;

- search is performed in a Docker container running on CPU (single machine) and very few GBs of RAM are available; we can instead rely on a machine with more RAM to build the index;

- accuracy is more important than speed: ideally we’d like to have exact results;

- we plan to perform several searches (>10000) in the lifetime of an index.

To play with a realistic dataset, let’s use the GIST 1M vector dataset (GIST vectors can be used in computer vision to represent entire images). We can download and inflate the dataset with a Linux shell using wget and tar:

wget ftp://ftp.irisa.fr/local/texmex/corpus/gist.tar.gz

tar -xzvf gist.tar.gz

Moving to a Python shell, with appropriate helper functions, one can read the file gist_base.fvecs (3.57 GB in size) into a numpy array xb of shape (1000000, 960):

xb = fvecs_read("./gist/gist_base.fvecs")

As we plan to perform several searches (see above), we can assume that precomputing can be helpful. As we are limited by RAM but the dataset is not huge, we use pruning but not compression. We thus opt for a IVF4000,Flat index that organizes the vectors in 4000 buckets in $d=960$ dimensional space:

index = faiss.index_factory(xb.shape[1], "IVF4000,Flat")

We then need to train the index so to cluster the vectors that are added to it.

Instead of doing this as above (i.e. with index.train(xb) and index.add(xb)), we train the index with a subset of the vectors xb[0:batch_size], add vectors to sub-blocks of the index in batches of 100000 vectors each, as this allows to limit RAM consumption at search time (see also demo_ondisk_ivf.py in the faiss GitHub repository):

batch_size = 100000

index.train(xb[0:batch_size])

faiss.write_index(index, "trained.index")

n_batches = xb.shape[0] // batch_size

for i in range(n_batches):

index = faiss.read_index("trained.index")

index.add_with_ids(xb[i * batch_size:(i + 1) * batch_size], np.arange(i * batch_size, (i + 1) * batch_size))

faiss.write_index(index, f"block_{i}.index")

Finally, we can save the final index to disk with:

index = faiss.read_index("trained.index")

block_fnames = [f"block_{b}.index" for b in range(n_batches)]

merge_ondisk(index, block_fnames, "merged_index.ivfdata")

faiss.write_index(index, "populated.index")

While the above construction is a bit cumbersome and slow, it can be repaid off if we perform enough searches later down the line.

To re-read the index from disk we can use

index = faiss.read_index("populated.index")

May we need to recover the i-th vector in xb, we could use the syntax

i = 42

index.make_direct_map()

index.reconstruct(i).reshape(1,-1).astype(np.float32)

Finally, we can perform the search for a set of 1000 query vectors xq. We carry out the search within a limited number of nprobe cells with

xq = fvecs_read("./gist/gist_query.fvecs")

index.nprobe = 80

distances, neighbors = index.search(xq, k)

The code above retrieves the correct result for the 1st nearest neighbor in 95% of the cases (better accuracy can be obtained by setting higher values of nprobe).

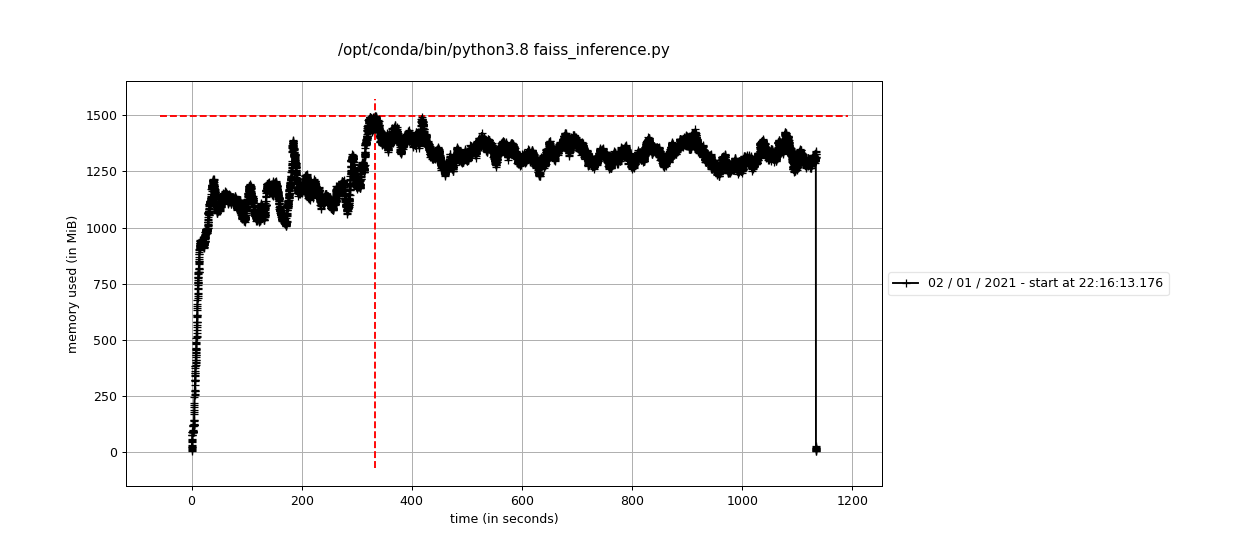

Memory consumption can be kept at bay: the search succeeds within a Docker container with RAM capped at 2GB, as shown by running the code with mprof run:

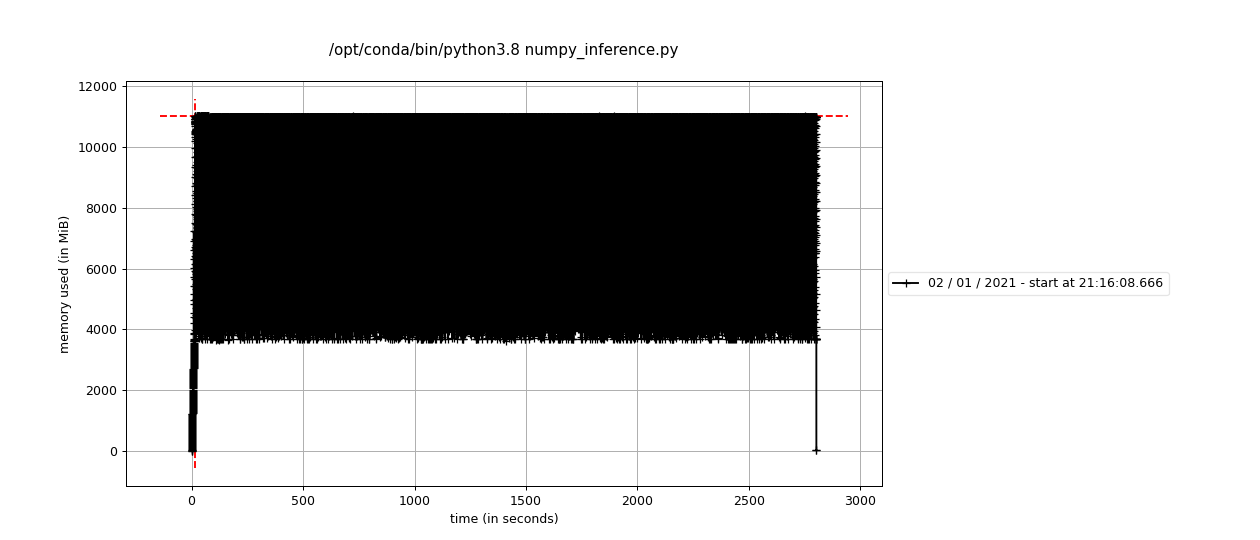

The equivalent numpy code needs more than 8GB to run (it crashes otherwise!), and runs slower:

The GIST dataset is not huge, but the example above shows that faiss can be helpful to tackle cases in which numpy or sklearn struggle, and can be modified (e.g. by using other indices) to handle even larger vector sets.

That’s it! The GIST example above can be reproduced using code on https://github.com/davidefiocco/faiss-on-disk-example.

Search on

The faiss documentation is on its GitHub wiki (the wiki contains also references to research work at the foundations of the library).

An introductory talk about faiss by its core devs can be found on YouTube, and a high-level intro is also in a FB engineering blogpost.

More code examples are available on the faiss GitHub repository.

The website ann-benchmarks.com contains the results of benchmarks run with different libraries for approximate nearest neighbors search (including faiss).

Another helpful GitHub repository containing faiss usage tips is https://github.com/matsui528/faiss_tips.

A nice tutorial on the library can be found at https://www.pinecone.io/learn/faiss-tutorial/ too. Enjoy!